Buddhism to Become Autonomous

People say that a spiritual master’s strength is the ability to make his students autonomous.

Whatever Jigme Rinpoche teaches during his courses, the process he applies is a reflection of this.

Listening

First, he transmits the instructions; we are, thus, in a situation of listening. He shows us how practicing the Buddha’s teaching is not an ordinary process. It does not occur like a project with goals, deadlines, and tasks to accomplish. In that case, we do everything we can to achieve our objectives, and we are disappointed when it doesn’t work and happy when it does. Rinpoche clearly explains that, in terms of spiritual practice, if we follow the instructions in a radical way, this will not work. It is important to apply the teachings based on our ability, to set ourselves to a training whose progression will be the opposite of what we imagined in the beginning. This, of course, requires flexibility. And, with time, we will go beyond training. In short, we are in a process of exploration and discovery.

Reflection

But listening to the teaching is not enough. In addition, Jigme Rinpoche creates situations for reflection; Dhagpo’s lamas support this dynamic by reviewing the day’s teaching with course participants in order to deepen our understanding of the meaning together. Rinpoche warns us that correct understanding isn’t something we can develop on short notice; it is the result of “slow and steady movement.” This means progressively transforming our habits based on unusual perspectives. “The path is not artificial. We cannot force ourselves to walk; it occurs naturally.” And this means seeing our dysfunction, identifying it with a new, direct look at ourselves. This vision can also include others. Again, he warns us, “understanding our functioning through practice does not liberate us immediately, but we will progressively experience fewer difficulties.” And therefore, more space to open to others and to understand them as well. This is how we establish the foundations of compassion. We must put energy into our development; “we need to put effort into reflecting on the teachings and into daily practice. It is important to remind ourselves that the teaching is liberating.”

Meditation

Between sessions of teaching and reflection, guided meditations allow us to familiarize ourselves with non-distraction. Within the exercise of meditation, we bump up against extremes: at times relaxed but inattentive; at times aware but tense; at times uncomfortable but present; at times very comfortable but very distracted. Meditation is not about looking for a particular state (whatever that may be), nor about ceasing the mind’s movement (whether it is busy or not), nor about creating this or that experience (which is so easy to do). We can summarize the practice of meditation in Rinpoche’s words: “training the mind not to follow its perpetual movement—whether it be thoughts, ideas, memories, images, etc. At the same time, the mind is aware, present to itself.”

Practitioners who have undergone the guided meditation training lead these sessions. The exploration continues, whether it be for the session leaders who continue their training and refine their practice or for the course participants who delve into calm and movement. The principle is for clarity to be present for each of us. So, let’s take the time…

Study

As an example of the results of consistent studies, Rinpoche asked several of Dhagpo’s resident volunteers who have studied with Khenpo Chodrak Rinpoche to share their knowledge with the public. During several recent courses, they have given detailed explanations of the five aggregates as they are explained in Mipham Rinpoche’s (1846–1912) Gateway to Knowledge. Because they are occupied with the activity of running the center, the residents cannot participate in the courses and teachings proposed in Dhagpo’s program. However, they do receive daily training in study and meditation practice. As part of this program, Khenpo Chodrak Rinpoche, a great scholar in the Kagyu lineage, has been training them in the essential notions of Buddhist philosophy for several years. All those present for their explanations can appreciate their relaxed yet thorough and disciplined manner of sharing the concepts they have learned. It shows how dharma transmission is a constant, living process that benefits from application and being tested.

Translation

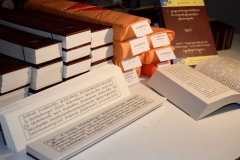

Whether it be the text on the aggregates or the commentary that Jigme Rinpoche uses for his teaching on universal compassion, the work is translated at Dhagpo by a small team connected to the Institute’s library and Kundreul Ling monastery in Auvergne. It is yet another example of progressive development. In this case, the goal is not to produce a definitive translation as quickly as possible. Once again, we find value in the process itself; here, as a way to understand what translation really means. The trick is to avoid fixating on the words in order to progressively discover the meaning of the teaching. With support from Rinpoche and visiting scholars, the members of the translation team perpetually continue their training in both written translation and oral interpreting. In some cases, course participants directly receive the translated texts as a study tool. In others, the translations become small handbooks that we can find at Dhagpo’s bookstore. And, in certain cases, we publish very finalized work as books.

A Process of Liberation

People say that a spiritual master’s strength is the ability to make his students autonomous. When looking at the different aspects of Jigme Rinpoche’s courses, it becomes apparent that everyone involved—teachers, practitioners, residents, and course participants—is learning about study, meditation, and service to others from wherever he or she is, in order to make the Buddha’s teaching a true process of liberation.

Puntso, Head of Dhagpo’s Program